See Part 1 of this Series on Purchase and Sale Policy here

When Mario of Super Mario Brothers hits an object and a coin comes out, this is probably not what literally is happening. Instead, from Mario’s point of view there are objects he finds in everyday life that have a monetary value and he manages to get some money for them (thievery can be lucrative). He may be selling these objects, but more than likely he’s pawning them. The world of collateral isn’t something we think about often in our day to day lives. We may think about it a little bit when taking a mortgage or in frustration at the inability to get access to credit ourselves. But overall, collateral is just not something we spend a lot of time thinking about. If collateral itself is relatively obscure, the collateral policies of central banks are much, much more obscure. They’re even obscure among monetary policy experts. Kjell Nyborg’s excellent book on the subject is entitled “Collateral Frameworks: the Open Secret of Central Banks”. Looking through the lens of collateral makes for quite a different vision. When we look at the world with this vision, what pops out is not just the sale price of assets, but their collateral price. Some things are hard to sell, but easy to pledge as collateral. In short, we see what we can coin into money in any way possible. We see the world like Mario.

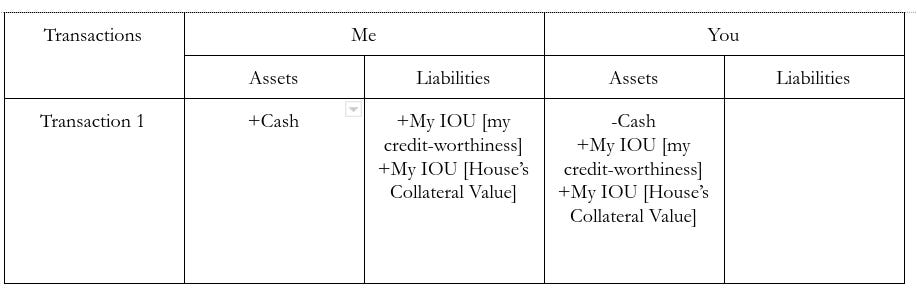

To start, let’s simply run through the transactions involved with Mario pawning something he’s “found”. As you’ll see below. A pawn transaction is actually quite complex for something that you might think of as basic.

To simplify the use of these “T accounts” I’m going to use “IOUC” to mean “I Owe yoU Collateral”. As you can see, Mario and the Pawnshop have swapped 2 items and 2 IOUs. Mario promises to repay the loan of cash, while the pawnshop promises to return the collateral to Mario when the loan is paid off. That’s quite a lot of transactions for an individual visit to the pawnshop! This is what is known as a repurchase or (repo) agreement. Other forms of collateral lending are simpler in that they embed the collateral into the IOU rather than involving the collateral being sold in exchange for an IOUC. See, for example, the mortgage below.

While this isn’t how the transaction would be accounted for officially, we can think of this as really me swapping two distinct IOUs for cash. One is the IOU that has value based on my likelihood of repayment. The other is the IOU that is based on the likelihood that the house can be sold and the proceeds will be sufficient to pay off the mortgage.

The less creditworthy the borrower is, the more collateral they need to get credit. In essence, collateral worthiness can replace credit worthiness. In extreme cases, a completely uncreditworthy borrower can get credit if the lender has enough faith in the collateral. During the height of the housing boom, collateral worthiness clearly replaced credit worthiness in many mortgages that were made. Of course, fraud (both lender and appraisal fraud) helped along that process greatly. When producible physical assets have high and stable collateral values, even when their sale prices are low or sale markets have few participants and infrequent transactions, their collateral value drives production of more of them. High and stable collateral values appear most often when the entity that accepts the item in question as collateral is the central bank. As Nyborg says, “As an extreme example, if central bank money is available only against igloos, or igloo-backed securities, igloos will be built”.

There is an extremely critical point that is implicit in Nyborg’s statement- a central bank which decides to accept a wider variety of items as collateral on better terms is choosing to loosen its monetary policy stance. Yet in most monetary policy discussions, this is rarely commented on. Instead, commentators tend to look at purchase and sale policy or interest rates to decide if monetary policy is lax or tight. To see the problems with this, let’s run through an extreme thought experiment.

Imagine a world where interest rates are negative 30% but individual households can only get loans if they pledge a 10 million dollar government security as collateral. Every instinct we have tells us that that is an insanely loose monetary policy. In reality, the access to credit for ordinary households has become non-existent in this scenario and is far more restrictive than anything anyone has ever experienced in modern history. Imagine again that this is also true for businesses, but there is an extreme shortage of treasury securities. The treasury securities that do exist are held by institutional investors, desperate to get any “risk free” asset that they can. They aren’t letting go of them. Credit has basically become non-existent in this scenario, despite such negative interest rates signaling to us that “credit is loose”. This is of course a very extreme scenario. However, the essential point is quite true- tight money can coincide with loose interest rate policy.

Another way of grasping how important the collateral policy is is to simply look at the Federal Reserve crisis facilities. Some are purchase facilities but the vast majority of facilities are about expanding what is collateral for loans. The idea behind them is that in normal times we may not want to backstop originating certain types of loans- or encouraging loans that use certain forms of collateral- but in a crisis we’re not willing to let entities (whether they be large bank holding companies or non-bank financial institutions) to fail in large numbers. As a result, we will finance asset holdings we wouldn’t otherwise finance by expanding what is acceptable collateral and expanding the list of who is an eligible borrower from the central bank. The problem- as Hyman Minsky famously observed- is that the expectation that central banks will expand the list of acceptable collateral (called the “collateral schedule'') and eligible borrowers is partially what makes those entities creditworthy and those assets collateral worthy in good times. On the other hand, when the collateral schedule shrinks again, credit tightens. It is overlooked that even as large scale purchases of treasury securities continued, Federal Reserve monetary policy tightened as the crisis era facilities were wound down between 2009 and 2010.

There is a lot more to say about central bank collateral policy (especially the role of rating agencies in collateral policy) but this is sufficient for now. The five major points we’ve covered are

Collateral is a critical part of central banking that is often neglected

There are different ways of providing collateral for a loan with important legal differences

Borrowers need some combination of personal creditworthiness and collateral-worthy assets to get loans

Preferential treatment towards a certain type of collateral by a central bank will lead to more private generation of that collateral

A tight collateral schedule can mean tight monetary policy even if interest rates are low.

Next week we’ll be talking about payments systems.

See you next week!