Have Nonfinancial Businesses Generally Turned to Financial Investments for Profits?

Guest Piece by Joel Rabinovich

This is a Notes On the Crises Guest piece by Joel Rabinovich

Joel Rabinovich is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Economic Division of Leeds University Business School

While the Great Financial Crisis famously brought to the frontline the aggressive lending practices that many of the largest banks had been engaged in during previous years, it also exposed new practices from other, unexpected, players: the nonfinancial sector.

This phenomenon can be located within the broader context in which the nonfinancial business sector in OECD countries have decreased the rate at which they reinvest profits into productive activities, something that with its cyclical fluctuations can be traced back to the early 1980s — and more clearly to the early 2000s. Contrary to what could be expected, part of those funds have been channeled into different types of financial assets rather than investing them into machinery, plants and equipment.

Hence, different companies started to engage in what were seen before as activities typically carried out by banks, sometimes holding and trading assets, others even lending to their customers. An example of this is the recent case of Tesla investing $1.5 billion in bitcoins in order to “diversify and maximise” returns on its cash, with Elon Musk supporting this decision by saying that: “when fiat currency has negative real interest, only a fool wouldn’t look elsewhere.”

Far from denying these trends, the questions I will address in this piece are rather different:

1) How widespread these practices are, and 2) Whether or not non-financial businesses are increasingly acquiring financial assets, in order to obtain a higher proportion of their total income out of them.

The unexpected financial players

Amid the turmoil of the crisis, the case of GE Capital — the financial arm of General Electric — featured prominently. Starting in the 1930s as credit provider for GE appliances, GE Capital would later evolve through its divisions into commercial aviation, energy (main productive units of GE) — but also ultimately into residential mortgages. It ranked among the top 20 financial companies in asset size between 1986 and 2014, reaching the 2nd position in 1993. It stayed within the top 6 for most of the 1990s and early 2000s. They hold the position along with Citigroup, Bank of America, JP Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley and Merrill Lynch. During that period, revenue generated from GE Capital represented an average of 40% of GE total income. Ford also had its credit division (Ford Motor Credit Company) among the top 30 financial institutions by assets for most of the 1980s and 1990s.

There are also cases in which nonfinancial firms directly own a hedge fund to manage their cash reserves, like Apple’s Braeburn Capital, which handles most of Apple’s 191 billion dollars in cash and short and long term securities. The maximum amount held by this fund was reached in 2017, with almost 270 billion. At that moment, they represented 30% of Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley total assets, making it one of the world’s largest investment companies. That amount of liquid financial assets was also higher than the stock of foreign reserves of developed countries such as Germany, the United Kingdom and France, and developing economies such as Thailand, Mexico and Indonesia.

The financial turn of accumulation hypothesis

These apparent common practices between the financial and nonfinancial sectors have led to the claim that the latter has become increasingly financialized. The term ‘financialization’ is mostly used to define broader dynamics affecting the whole economy, highlighting the increasing role of financial institutions and financial practices. In this context, the nonfinancial sector is therefore said to be financialized to indicate what could be defined as a partial replication of the financial sector business model. By doing this, nonfinancial traditional sources of income linked to the production and sale of goods and services would be replaced by financial income. In other words, linked to lending, holding and trading financial assets. This is what I have called the financial turn of accumulation hypothesis.

This hypothesis generalizes particular and prominent cases — such as the one described before for General Electric — to an aggregate trend. From this view, nonfinancial firms, especially the biggest and more internationalized ones, are increasingly acquiring financial assets. They do this in order to obtain a higher proportion of their income out of them. The evidence used to sustain this hypothesis has been based, therefore, on two pillars. First, an increasing proportion of financial assets in the balance sheets of nonfinancial corporations. And second, an increasing proportion of financial income, over nonfinancial corporations’ total income.

The first part of the hypothesis is undeniably true: the proportion of financial assets over total assets has increased during the last half-century as is shown in Exhibit 1. Financial assets include cash and short-term investments, investments in other firms and other current assets. The magnitude of the rise is also undeniable: almost doubling from 1970 to 2018. The growth is mostly driven by the former category, which consists of liquid financial assets, be that in cash or securities readily transferable to cash.

Exhibit 1: Selected financial assets, listed non-financial corporations

Note: assets measured as a proportion of total assets.

Source: Compustat.

Shortfall

While the first part of the hypothesis can be easily verified, to really prove the financial turn of accumulation hypothesis, it has to be demonstrated that those financial assets are actually generating a flow of income that either complements traditional nonfinancial sources, or replaces them. In fact, ideally one would like to demonstrate that the turn to financial accumulation is also lucrative. That it generates positive net income, i.e., that financial sources income are higher than the financial expense.

Accurate information to do so, however, is difficult to get. An exact measure of financial profitability would need to consider only those financial expenses limited to the cost of acquiring, holding and trading financial assets. Considering all financial expenses would overestimate. For instance, financial expenses include interest from debt taken to finance productive activities. Available information (shown in Exhibit 2) only provides a rough idea of the financial position of NFCs.

Exhibit 2: financial income, all US non-financial corporations

Note: financial flows measured as a proportion of total receipts.

Source: IRS

Shaded areas indicate the evolution and weight of different sources of financial income, over the total income generated by non-financial corporations. Those different sources include interest income, net capital gains and dividends from foreign and domestic companies. It is important to highlight that dividends are usually considered to be part of financial income — although they may perfectly be related to non-financial activities done by subsidiaries. In any case, even if they are taken into account, financial income is usually below 2.5%, and it only surpassed the barrier of 3% in 2005 due to a tax holiday on repatriated profits. If only capital gains and interests are taken into account, the aggregate is usually below 2%. Moreover, financial income presents a clear upward trend, continuing until the beginnings of the 1990s. It then oscillates until 2005, and then declines.

Exhibit 2 also includes interests paid by nonfinancial firms. Except in 2005, interest paid was always higher than all measures of financial income combined. Even though computing all interests paid overestimates the cost of holding and trading financial assets, it can give an approximate idea concerning the worth of nonfinancial firms. On average, they have not generated a substantial amount of income from engaging in financial assets holding and trading.

However, we shouldn’t oversimplify. Saying this is not the same as claiming that non-financial firms are not benefiting from the financial engineering involved in holding those assets — both directly and indirectly.

So, why are nonfinancial corporations increasing their financial holdings?

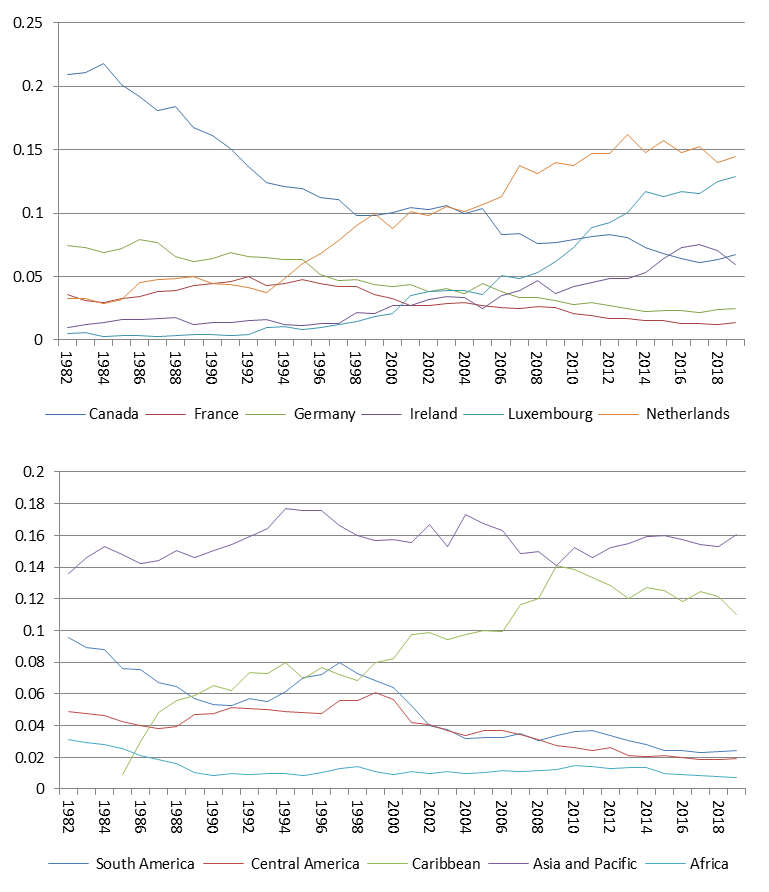

Although the objective of this note is not to dig into the ultimate reason for increasing liquid financial holdings, there is substantial evidence suggesting that these are being held in low-tax jurisdictions. Exhibit 3 indicates the stock of US Direct Investment held in different countries and regions, and clearly shows that the only places that portray an increase are so-called tax havens. Far from the typical, outdated representation of FDI as a synonym of investment in plant, equipment and machinery. Exhibit 3 presents a more realistic picture of FDI. It really serves as a financially engineered mechanism to pay fewer taxes. The basics of this mechanism involve parking profits in these jurisdictions that end up being accumulated into the stocks shown in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 3: US Direct Investment abroad in selected OECD countries (upper panel) and selected developing regions (lower panel)

Note: percentages calculated as a proportion of total stock in all countries.

Source: BEA.

Going back to the financial turn of accumulation hypothesis and its two pillars: whereas increasing financial assets was proven to be quantitatively significant, the same cannot be said of increasing financial income. In terms of the company-specific examples, Apple, although extreme, seems to be a more accurate example of the general trend than GE, with large holdings of financial assets — but no massive income generated out of them.

If one could think of ways to reformulate the hypothesis, the most valid one would probably focus on (tax-related) costs, rather than income. In other words, corporations which engage in complex financial practices in order to avoid corporate taxes have likely become more financial than their mid-century counterparts. The increasing importance of intellectual property rights to corporate profits and their complex international legal structuring is another activity that could be reasonably characterized as “financialized”.

However, the tax-avoidant and intellectual-propertied corporation is a far cry from the nonfinancial corporation making large profits investing in financial (or quasi-financial) assets. Meanwhile, plenty of companies still make profits investing in physical objects and product-related technological development. In short, significant anecdotes notwithstanding — financial investments aren’t taking over businesses.