Much Ado About Checks

How Do You Solve a Problem like Direct Payments?

We finally have a Covid relief package! After substantial grandstanding President Trump finally signed off on a Covid relief bill late Sunday night. I had a version of this piece written by the middle of last week, but became concerned about publishing it when the fate of the second round of fiscal support to the economy remained in such doubt. Over the week, I’ve also spent a lot of time thinking about this controversy over direct checks. Mostly, I’ve been reflecting over my conflicted opinions over how this controversy has played out. But before I get to my mixed feelings, first it’s worth running through the fiscal measures the Covid relief package actually contains.

The headache of sorting out these details have been magnified by the decision to include the Coronavirus relief package in the annual appropriations legislation. Recall that outside of Social Security, Medicare and a few other programs, most types of government spending are funded by this kind of legislation: which “appropriates” federal money to various different areas. This funding most often comes through an annual budget, referred to as “annual appropriations”. This term is used because congress is “appropriating” the money (or earmarking it). Annual appropriations were overdue for fiscal year 2021, and it was ultimately the need to pass annual appropriations which compelled Mitch McConnell and Republicans to negotiate more seriously over a Covid relief package (as well as a concern about the Georgia senate runoffs). The same factor compelled Nancy Pelosi and Democrats to buckle over their previous sticking points. In other words: some consensus was required, to avoid the federal government grinding to a standstill indefinitely. This is a classic case of “fiscal cliffication" that I’ve been writing about for a while now.

The downside, of course, is that this led to people pointing out random provisions of the entire bill, then rhetorically asking what that provision had to do with Covid relief. It has become a mainstay in social media to quote some part of the broader annual appropriations that the poster finds objectionable, with the refrain: “what does this have to do with coronavirus relief???”.

To the credit of these innumerable commentators, we certainly don’t want a situation where the confusing structure of federal spending allows politicians to avoid accountability. It is certainly the case that annual appropriations should, in general, get far more scrutiny. Yet I don’t think it enhances public understanding of the legislative process to conflate annual appropriations with the two distinct sections of the bill devoted to coronavirus related spending. Rather than increasing critical understanding and scrutiny of congress, this framing makes legislatures seem more irrational than they actually are and breeds confused and frustrated disengagement . This point was more difficult to defend before conflating these provisions with the Coronavirus relief package ended up being one of Trump’s two main justifications for opposing the legislation last Tuesday.

Let’s try to get a more precise view of what’s going on than we can find from President Trump.

The Coronavirus relief package itself (Division M and Division N of the appropriations bill) is all directly related to the economic fallout of Coronavirus. I’ve made a PDF of just these sections (which totals 240 pages), as I haven’t seen anyone else do that. You can find that PDF here. The package adds up to nearly 900 billion dollars in fiscal “spending”.

I found the wikipedia entry summary detailed and accurate, so I’m simply going to quote it here:

$325 billion for small businesses.

$284 billion in forgivable loans via the Paycheck Protection Program

$20 billion for businesses in low-income communities

$15 billion for economically endangered live venues, movie theaters and museums

$166 billion for a $600 stimulus check, for most Americans with an adjusted gross income lower than $75,000

$120 billion for an extension of increased federal unemployment benefits ($300 a week until March 14, 2021)

$82 billion for schools and universities, including $54 billion to public K-12 schools, $23 billion for higher education; $4 billion to a Governors Emergency Education Relief Fund; and slightly under $1 billion for Native American schools

$69 billion for vaccines, testing, and health providers

Vaccine and treatment procurement and distribution, as well as a strategic stockpile, received over $30 billion.

Testing, contact tracing, and mitigation received $22 billion.

Health care providers received $9 billion.

Mental health received $4.5 billion.

$25 billion for a federal aid to state and local governments for rental assistance programs (also covering rent arrears, utilities, and home energy costs)

$13 billion to increase the monthly Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP/food stamp) benefit by 15% through June 30, 2021.

$13 billion round of direct payments to the farming and ranching industry,] including

About $5 billion for payments of $20 an acre for row crop producers, which (according to an American Farm Bureau Federation analysis) would go to producers of corn ($1.8 billion), soybeans ($1.7 billion), wheat ($890 million), and cotton ($240 million).

Up to $1 billion for livestock and poultry farmers, plus certain "plus-up" payments for cattle producers

$470 million for dairy producers, plus additional $400 million for the USDA to purchase milk for processing into dairy products for donation to food banks

$60 million for small meat and poultry processors

$10 billion for child care (specifically, the Child Care Development Block Grant program)

$10 billion for the U.S. Postal Service (in the form of forgiveness of a previous federal loan)

None of these are particularly objectionable. Even the Payroll Protection Program, which has had a very mixed experience, is not simply a “giveaway” to businesses without public benefits.

The big problem with this legislation is simply that the overall dollar amount is too small. As a result, various elements are significantly inadequate. Most glaringly, there is no general state and local government aid. The unemployment insurance extension and re-expansions are both too small. The main non-fiscal provision is that it extends the eviction moratorium by a mere month, which is very inadequate (I will cover the Federal Reserve provisions in the new year). Millions of renters owe thousands upon thousands in “rent debt” through no fault of their own and 25 billion dollars in “rental assistance” administered by state and local governments does not fill that hole at all. And, yes, the direct checks are too small.

Which brings us to those “checks”. Trump’s other main objection to the legislation, besides picking at general appropriations provisions, was famously that the one-off direct payments were too small. I joked on twitter that he was listening to the public’s outrage, and responding. There is a grain of truth to this: Trump is infamous for picking up on social media trends, and then regurgitating them in his rhetoric. This is crude and embarrassing in Trumpian form, but underneath it is a political issue we can’t dismiss.

I am becoming increasingly worried that as public discourse becomes more and more centered around using whether, and how large, “stimulus” checks are. This is becoming a proxy for how good or bad legislation is. If this continues to be established as a benchmark, we will get worse and worse legislation. That kind of process can easily be gamed, and lead to less support for the most vulnerable. It can also result in neglect of critical public policy priorities, like state and local government funding.

Understanding the importance of this is crucial for a strong response to the Coronavirus in 2021. It is still not well understood that state and local governments have been consistently reopening far too prematurely because of budgetary concerns. They need extraordinary support to stop doing that. The stakes could not be higher: stopping premature reopenings means avoiding and suppressing the community spread causing thousands upon thousands of deaths every week in the United States.

It’s not hard to imagine that the political lesson politicians are learning from this experience is that they can neglect important priorities that are more abstract such as state and local government aid and get less scrutiny towards others if future “economic support” legislation is largely devoted to significant direct individual payments.

Of course, as I write Mitch McConnell is blocking making the checks $2000 dollars, rather than $600 dollars. Yet, that doesn’t preclude future republican leadership getting “innovative”. Nor does it stop future centrist democratic politicians from getting more comfortable with direct payments, as an alternative to more fundamental economic transformations.

Yet, as I’ve reflected on this week it's hard to be frustrated with the outrage over check size. The United States administrative apparatus has been truly neglected, decaying and capricious for generations. We have 50 state unemployment insurance systems with different rules and in varying states of disrepair that can be difficult to update or fix, and are often impossible to interact with for individuals who need them. You can suddenly end up owing tens of thousands of dollars because of allegedly “incorrectly paid benefits”, through no fault of your own. If you’ve waited five months to get unemployment insurance, why wouldn’t funds simply directly deposited into your bank account feel more “real” and immediate?

The painful lesson of Obamacare is that if the most salient part of your reform program (e.g. marketplace exchanges) is burdensome, difficult to use and easy to use incorrectly, it is difficult to convince people that they are truly benefiting from your legislation. This doesn’t mean you have to avoid means testing. While the direct “economic impact” payments are often discussed as if they’re universal, they are means tested (as detailed above). But accessing them has been, for the most part, far less burdensome than accessing programs like unemployment insurance.

The only way to make unemployment insurance a more salient political issue would be for some major political force to champion it. Doing so would require making accessing the benefit as painless as getting a direct check — or at least promising that that is your goal. That would, in turn, require proposing that we federalize unemployment insurance — a move which has additional fiscal and countercyclical benefits. But who would take on such a reform program?

This is certainly not the kind of thinking that drove interest in nominating President-Elect Biden, nor does it seem like the kind of political issue that he or the people around him are inclined to take on. Far from being an easy ‘bipartisan’ win, radical reform to unemployment insurance would require a high level of conflict with Republicans, and assertive rhetoric about what residents of the United States deserve. The additional $600 dollars a week attached by the CARES act to unemployment benefits was a great test case for how effectively generous income replacement policies could be. Either new organized political forces need to emerge to reestablish them, or Democratic party leadership needs to pivot away from its conventional strategies for gleaning support. This would mean a shift towards a more positive vision, built around truly providing the public government protection.

In short, we’re getting checks.

To be clear, the problem with this second round of fiscal support is not that the support to the overall economy is inadequate to avoid a depression or extended recession. Even with vaccine timeline delays, as long as that distribution gets fully funded in 2021 (a big if), this will probably set us up for an economic recovery over the course of the Fall of 2021, and Spring of 2022. The problem is that this is not adequate to save many easily saveable lives. Nor will it prevent those most affected from this crisis losing their livelihood.

Recall that millions of people were foreclosed on after the Great Financial Crisis. While the subsequent recovery was grindingly slow and anemic, profits recovered, and we did eventually get within striking distance of a high employment economy. That process will probably be quicker this time, as this is a different kind of economic issue. Crucially, household balance sheets (and even most non-service business balance sheets) are generally stronger this time around.

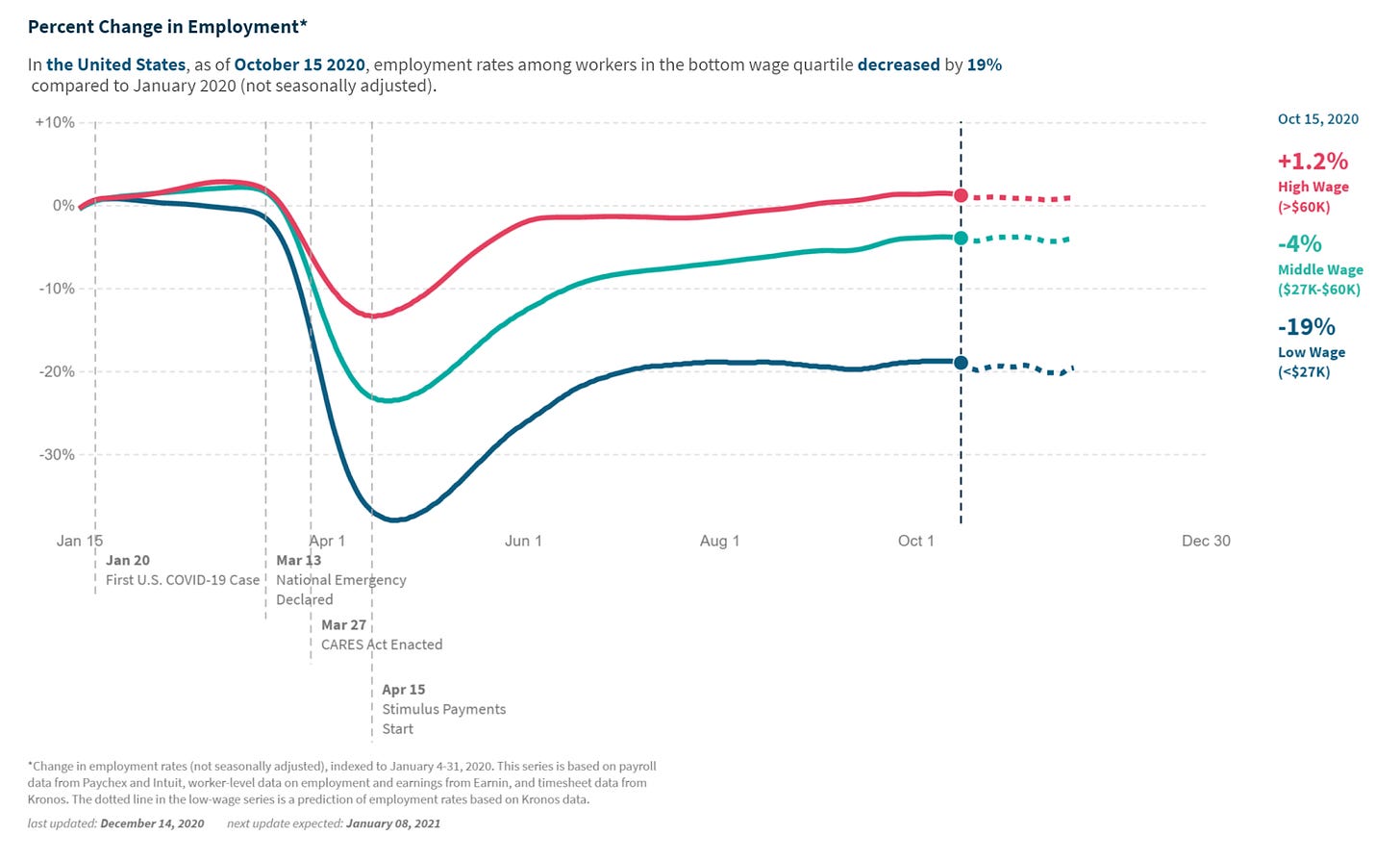

Remember that this has been a services-led depression, and services are filled with low and lower-middle income individuals. A project of Howard University’s Opportunity Insights project called “Track the Recovery” estimates that those who make over 60,000 a year have actually seen employment rise since January, while those who make less than 27,000 are still 19% below the employment level they had in January. Survey evidence suggests high wage people are much more likely to have “fully recovered” than low wage people.

Given that low income people consequently earn such a relatively tiny percentage of aggregate household income (almost by definition in such a profoundly unequal society), there is no strong relationship between the social scarring they experience with the overall state of “the economy” as captured by national income statistics or aggregate productivity. Illness, foreclosure, eviction and even death experienced by low income households are not measured by these statistics. Even unemployment rate statistics can miss the mark. Expansionary economic policy can serve its salutary role, while economic support policies to prevent death and hardship remain missing in action.

What concerns me more than anything else is that with the vaccines in sight, media attention has skipped ahead to the end of all this. But today tens of thousands of people are still in danger of dying because we’re not providing the state and local aid (and direct resource provisioning) required to make that happen. That is why I was glad that I got the chance to go on Bloomberg TV Monday to say as much.

The urgency of state and local government aid has (with notable exceptions such as my interview above) disappeared almost entirely from media, policy and public discourse in a wave of overoptimistic vaccine news. Meanwhile the prospect of saving lives through lockdowns is more, not less, urgent as we find ourselves on the precipice of vaccinating the population. It has not been widely understood that if these vaccines do not provide protection from infection (and not merely from disease), social distancing and masks are still important even as more and more people are vaccinated. We need to sustain the measures taken (unreliably…) in 2020 into the new year, if we hope to save the lives of the most vulnerable. It’s seems unlikely as of right now that that will happen. As the depression fades, the Coronavirus crisis loses its ability to focus attention on public health, and saving lives.

In the midst of all this, the appeal of “you’ve failed, send us a big check” becomes readily apparent.