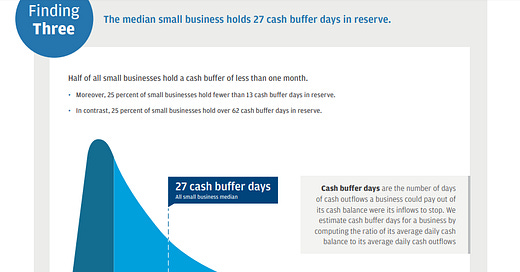

One of the things that the global coronavirus depression has really revealed is how little cash medium sized and small businesses have on hand, especially relative to their monthly costs. As the situation became acute, a September 2016 report from the J.P. Morgan Chase Institute called “Cash Is King” began to recirculate in the press which studied an 600 thousand small businesses and showed how numerous businesses in their sample had less than 27 days of cash on hand.

Even large corporations which have much more cash on hand relative to their monthly costs than smaller businesses still seem to by and large have relatively limited amounts of “cash on hand”,The natural response was obvious- businesses should be required to hold more liquid assets relative to their outflows. Is this the right response though? Mike Bird of the Wall Street Journal thinks not. In a column entitled “Making Corporate America Hold Cash Is the Wrong Way to Prepare for Crises”, Bird challenges this emerging conventional wisdom.

The essential analytical point of Bird’s piece is sound. For the business sector as a whole to increase their holdings of liquid financial assets, some other sector (or multiple sectors) have to either reduce their holdings of liquid financial assets or provide liquid financial assets to the business sector by going further into debt. Bird illustrates this point more tangibly by showing a sectoral financial balances chart which is the standard fare of Post-Keynesian or Modern Monetary Theory analysis. As an aside, it is truly remarkable how standard and uncontroversial this kind of argumentation has become in the last decade.

Given that households going deeper in debt would simply transfer vulnerabilities to them and similar is true of foreign borrowers, Bird argues that a consistent rise in business saving would require larger fiscal deficits from the United States. If this didn’t occur, the attempt to save money at the individual level would frustrate the attempts to accumulate savings at the sectoral level. This is true. He then goes on to argue that this means there is little difference between raising corporate taxes in the good times, bailing out corporations in crises on the one hand and managing countercyclical (anti-recessionary) liquidity regulations on the other.

I have a number of problems with this argument. The most obvious is that liquidity regulations would be structured very differently from our current suite of corporate taxes. Changes in reported profits would have no effect on the entity’s requirement to accumulate liquid assets. At best, they may see the requirement to hold a certain amount of balances by the end of quarter or end of year delayed in implementation. Dividends and buybacks could be suspended up until the required cash balances are accumulated whereas corporate taxes only reduce payouts if the business doesn’t cut some of its other myriad payment commitments.

I also question the idea that liquidity regulations would eliminate the need for a crisis response to support their balance sheets by the government. Instead, it seems to me they make crises responses more well thought out and timely by giving a cash buffer period between crisis and total ruin. The problem with Bird’s logic is well illustrated by where we do have liquidity requirements- financial institutions. The Federal Reserve is a government administrative agency with the widest discretion in decision making afforded to it. It supplies liquidity to the banking system and wider financial markets every day. Yet, the U.S. still followed Basel III. There is still wide agreement among central bankers that accumulations of high quality liquid assets which provide the capacity to meet at least 30 days (if not more) of payments without extensive central bank intervention is desirable. This is despite the fact that central banks have some of the easiest and most direct tools to originate loans and provide support across the economy.

If the Federal Reserve needs thirty days to respond, congress and other agencies certainly need 60 days or longer to respond. Liquidity regulations on non-financial businesses provide a distinct advantage in this case. Incidentally, the debate over liquidity regulations on non-financial businesses illustrates a point I’ve been hammering for over a year now- even under conditions of presumed “full employment”- there are a wide variety of non-fiscal demand offsets available to disemploy people and physical resources which can be redeployed with new spending.

Liquidity regulations are monetary policy tools which politically are far easier to entrust to administrative agencies to discretionarily change than taxes. Admittedly, liquidity regulations on non-financial corporations blur the line between monetary policy and fiscal policy. Yet, there are important differences. I actually discuss this at length (along with my co-authors) in a long-delayed forthcoming report:

Finally, liquidity requirements on non-financial entities are an uncommonly discussed policy tool available for increasing the propensity to save of households and businesses. They work by directly acting on the actors that economic policy is interested in inducing more or less spending from. This is also an area where monetary policy can begin to resemble fiscal policy. For example, Keynes famously proposed a compulsory saving “tax” in How to Pay for the War. Keynes' proposal would work similarly to conventional taxes except individual taxpayers would be provided financial assets equal to their tax payments after the war had ended. Randall Wray and Yeva Nersisyan propose a similar compulsory saving tax as part of the Green New Deal today. The main difference between liquidity requirements as monetary policy versus compulsory saving fiscal policy is the legal design of the non-reciprocal obligation. Compulsory saving fiscal policies tend to require letting go of direct control over financial assets with limited or no ability to remit funds that can be used to purchase current goods and services.

Liquidity requirements meanwhile allow for the legal entity subject to them to keep control of their assets and simply check at specified periods whether there are sufficient funds in an account or on their audited financial statements to meet the requirements. Compulsory saving fiscal policies tend to be applied to households since there is little policy reason to allow greater discretion over financial assets to households and it is more difficult to supervise individual households allocation of financial assets. Liquidity regulation on non-financial corporations meanwhile may be preferable to conventional corporate taxes since they may be resisted less aggressively because they are perceived to be temporary. This relative lack of political resistance also comes from the possibility that non-financial corporations would have quite a substantial level of financial assets when liquidity requirements are eased, which is nothing like the situation corporate taxes leave corporations in.

To sum up, the necessity for the federal government to run a fiscal deficit to offset the demand-reducing effects of liquidity regulations on non-financial businesses is a feature, not a bug of liquidity regulations. If they become a part of the budgetary process- either directly, or indirectly by having Congress entrust the Federal Reserve/financial regulators with the responsibility to use this tool to prevent an overheating economy, this becomes a great way to “pay for” the Green New Deal.

Of course, there are administrative issues to consider. An attempt to apply this to small businesses would likely require reincorporation where the reincorporated entity needed to run payments through a government provided bank account. There may also need to be a reallocation of coordination rights towards small businesses so they can afford to accumulate that level of cash balances. Details for such a policy tool would need to be worked out and cut across a number of areas of law. Yet, nothing Bird says is convincing that liquidity requirements are necessarily inferior to corporate taxation. In this case, I think the public’s intuition is sound. We need businesses to save more and the presumed downsides- like bigger fiscal deficits- are not problems with these proposals. They are,in fact, features.